Page 3 of 8

1916 was spent producing generators and planning for such a large production of aeroengines which it would have had to be subcontracted to multiple external companies. Bradshaw was consequently in charge of both running production and developing innovative designs while the Government was submitting requests for experimental designs.

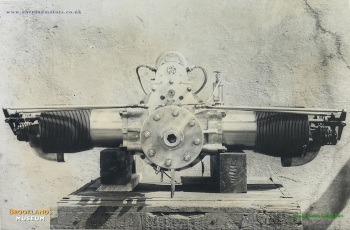

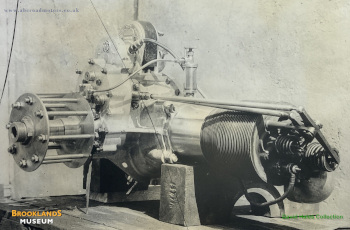

By November, a new aeroengine was made available for Government testing: the "Gnat".

It was a horizontally opposed twin, this time of just over three litres capacity, developing 45hp at 1,800rpm. There were great expectations for it with plans to produce 300 engines for the Russian Government and even involve Messrs Hanriot to start production in France. Some problems nevertheless did arise and the initial successful tests were only followed by two orders from the British Government for a total of 18 engines.

1916 A.B.C. Gnat engine - Curtesy of Brooklands Museum, David Hales Collection.

A Gnat was installed in the Sopwith Sparrow, and with radio control gear was taken to Laffan's Plain, near Farnborough. The order was given to start the engine, and the radio control panel, the work of Professor Lowe, was checked to make sure the desired signals were reaching the aircraft. All the military bigwigs stood waiting for the word to go, and expecting great things of what would prove a very useful weapon. The time came for the first flight, and the Sparrow started gaining speed across the grass. Fortunately, on this test run, the designed load of bombs was not being carried, the signals taking far too long to reach the craft. Frantic turning of controls merely sent the plane careering all over the place, generally in the direction of the portliest of the assembled bigwigs, and the machine eventually came to rest after running out of its gallon of fuel. Apart from this occasion, little was heard of the "Gnat" for the remainder of the hostilities.

Two unsuccessful designs followed the "Gnat". Firstly, Jack Emerson tried converting his motor cycle to run on paraffin, and secondly Harry Hawker bet Bradshaw that he could not design a radial aero engine with an even number of cylinders. Bradshaw took up the challenge, and using six Gnat cylinders on a common crankcase, brought about the "Mosquito", which not only had an even number of cylinders, but fired 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6. It did, however, prove unsatisfactory for production purposes.

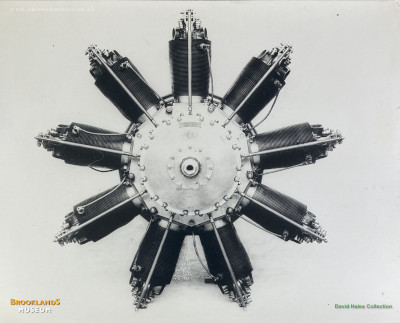

Next in the story come two ill-fated aero engines. The seven-cylinder radial "Wasp", with bore and stroke of 4 3/4 in. x 6 1/4 in. and rated at 160 h.p., was developed for fighter aircraft. Prototypes made from Bradshaw's designs by the Selsdon Engineering Co. Ltd. were fitted to Sopwith Snail, Salamander and Snipe aircraft, the latter with full fighting equipment achieving a maximum speed of 156 m.p.h. and climbing to 10,000 ft. in 4 1/2 min. In practice, although attaining a high degree of manoeuvrability, they proved somewhat under-powered, and an engine in excess of 300 h.p. was asked for. This request caused the "Dragonfly" to be built, a nine-cylinder of 320 h.p., the first of these being constructed by Guy Motors in 24 days. This was in February, 1918, and 14 more were made and put through preliminary tests in aircraft. At this time the Government were considering the best engine to put into mass production for the 1919 war programme, and having boobed previously by not including engines in the design or test stage, they did not wish to make the same mistake again. With this in mind, and the A.B.C. engine only just off the drawing board, they took some time in making their decision. The "Dragonfly" certainly looked the best on paper, so the final result was that over 11,000 were ordered. By the time the Armistice had been signed, only 14 were installed in aircraft, and over 1,000 engine units had been finished. Thirteen companies, listed below, had been involved with "Dragonfly" and, of the aircraft tested, the majority decision was that it was an unreliable engine. For this, Bradshaw claimed that certain alterations to the specification had been made by some of the manufacturers:

| Beardmore Aero Engines Ltd |

1,500 |

engines |

| Crossley Motors Ltd/ |

1,000 |

“ |

| Ransome, Sims & Jeffries |

500 |

“ |

| F. W. Berwick & Co. Ltd. |

1,000 |

“ |

| Belsize Motors Ltd. |

1,000 |

“ |

| Maudslay Eng. Co. Ltd. |

500 |

“ |

| Vulcan Motor & Eng. Co. Ltd. |

600 |

“ |

| Vickers Ltd. |

1,000 |

“ |

| Sheffield Simplex |

500 |

“ |

| Guy Motors |

600 |

“ |

| Clyno Eng. Co. |

500 |

“ |

| Ruston, Proctor & Co. Ltd. |

1,500 |

“ |

| Humber Ltd. |

850 |

“ |

| |

11,050 |

“ |

Radio-controlled Sopwith "Sparrow", with "Gnat" engine, Laffan's Plain, 1916. - Courtesy of Imperial War Museum

Production engines were heavier than the initial design, developing less power and vibrating badly. When flown, the aircraft were usually dogged by mechanical failure within a few hours. Even after revised pistons and cylinder heads had been designed and fitted by Prof. A. E. Gibson and S. D. Heron of the Royal Aircraft Establishment, the engine suffered from imbalance and synchronous torsional vibration, and to overcome this a complete redesign of the engine would have been necessary. When orders were cancelled, 1,147 engines had been made, of which 23 had been delivered up to the end of 1918, although production continued into 1919.

A.B.C. Dragonfly engine, 1918 - Curtesy of Brooklands Museum, David Hales Collection.

Aero engines was not the only aspect occupying Bradshaw's mind during the war. As far back as 1913, when the 500c.c. motor cycle engine was introduced, it was stated that a similar but larger version would be made for cycle car work. That year a capacity 900 c.c. was envisaged, and a combined fan-cum-flywheel would be used so that the complete power unit could be enclosed. In 1917 the engine grew to 1,094 c.c., a suitable gearbox had been designed, and so had an A.B.C. carburettor as described in April 1917 in an article on Motor Cycling and Light Car in June of the same year. By 1918 the transmission was said to be by friction discs, with final drive by chains (supposedly based on an American system) and quarter elliptic springs all round. A price of 100 guineas was mentioned. In 1919 the whole thing grew up to become the light car, of which more anon.

Before the war Bradshaw's most successful engines had been the horizontally-opposed twins. From 1917 onwards, the tendency was to concentrate on radials, so it is not altogether surprising to find him, like A. W. Reeves of Enfield-Allday, designing a radialengined car. This was to have had a five-cylinder engine mounted in a cowling similar to an aircraft, driving through a four-speed epicyclic gearbox incorporated in the flywheel, to a hinged rear axle with transverse quarter-elliptic springs as used on Sopwith aircraft.

1919 Nieuport L.C.1 with Dragonfly engine. Bradshaw is facing camera at right - Curtesy of Brooklands Museum, David Hales Collection.

Each half of the axle to have its own crown wheel, which would be driven by a communal bevel-ended prop shaft. Cone brakes were to be fitted, and the whole lot would be mounted in a tubular-framed chassis. To facilitate easier maintenance, the engine would be turned through 72 degrees to service each cylinder, and it was suggested that cheap stamped parts be used, which would be replaced fairly frequently, instead of maintaining an initially expensive item. Had other war-time developments been more successful, this novel 100 h.p. sports car might have reached the prototype stage, but as it was the design was shelved as an A.B.C. white elephant.

Meanwhile, it seems that an ABC subsidiary company, Walton Motors Ltd, formed in 1917 to concentrate on government contracts for aero engines, was instrumental in obtaining various parcels of land and premises close to their Hersham works, not least in August 1918 acquiring Hersham Lodge on Molesey Road, a mid-19th century mansion with seven acres of grounds and parkland suitable for converting to quite opulent offices with the possibility of building a large factory opposite the existing works off the Old Esher Road, Hersham.